“A 21st-century park is something very different from what Frederick Law Olmsted imagined when he won the competition for Central Park in the 19th century. We have the Internet, we have computer games, we have people flying to Hawaii for vacation, so a park in the 21st century has to be a wholly new kind of thing...I hope that we cast a wide enough net to get truly the first park of the 21st-century. Shelby Farms is certainly big enough to be something very special.”

“A 21st-century park is something very different from what Frederick Law Olmsted imagined when he won the competition for Central Park in the 19th century. We have the Internet, we have computer games, we have people flying to Hawaii for vacation, so a park in the 21st century has to be a wholly new kind of thing...I hope that we cast a wide enough net to get truly the first park of the 21st-century. Shelby Farms is certainly big enough to be something very special.”This little nugget of hubristic bombast comes from Alex Garvin, a former LMDC official (*ding*, red flag), in reference to his current project: a revamp of Shelby Farms Park, currently a twinkling RFQ in Memphis' eye. As it stands, the 4,500 acre park is currently used for a variety of recreational activities, as one might expect for such a huge space. The Shelby Farms Park Alliance describes the park as encompassing "lakes, paved and unpaved trails, forests, meadows, an Agricenter, a farmer’s market, a horse arena, a visitor center, rental horses, skate boarding, disc golf, dog off-leash area, senior gardens, a natural area with a river running through it, a restaurant, government offices and even a prison."

Heh...someone really knows how to end a list and start a party.

At any rate, Garvin was originally brought in to develop a master plan for the park that one can only assume was originally intended to have some sort of developed component. But Garvin's suggestion was to shape the rough natural spaces into the majestic, high-tech Versailles of the Future described at the start of this post. So now the RFQ is calling on L-archies big and small to come up with a way to turn a subdivision-ringed area that claims to be the largest urban park in America into a fully-functioning greenspace-masterpiece-extravaganza. Sounds like a thunderous disappointment waiting to happen, no?

There is naked ambition evident in Garvin's blustery prophesy of trailblazing landscape architecture; the Shelby Farms Park being (vaguely) envisioned is grand, expansive, and very,

very important. Yet the conflict of a park five times the size of Manhattan's Central is inherent in Garvin's own description of the challenge. The internet, computer games, and increasingly affordable transoceanic flights are all smaller pieces of the larger problem of technology's tendency to pull or even drive us apart. The logical solution to this problem, in terms of parks and other public spaces, would be to create engaging and inviting parks that, by design, bring people together. To achieve this, theoretically, a designer would need to work on a very human scale, focusing on details that would inspire interaction. To suggest that this can be done over a stretch of 4,500 acres implies a fairly rosy tint to one's glasses.

In fact, "humanly scaled" is most commonly used to describe the very un-grand side of urban design. The human scale is best suited to smaller spaces: pocket parks, plazas, paseos, grottos, playgrounds, and neighborhood gardens. These small spaces very frequently serve as local gathering places, reinforcing the importance of community in the larger context of the sprawling, technologically advanced megacities of the 21st century. They provide a sense of scale (there's that word again), reminding city dwellers that they are a part of something smaller than the cities in which they live. This is vital to city life, and these places are well-used because they are easy to fill up. That sounds a bit circuitous, but the fact is that the places most enjoyed in cities are the places where there are a lot of people around. A healthy amount of people-traffic makes us feel safe, and smaller public spaces are easier to keep busy, plain and simple.

That's not to say that large parks can't work. Central Park in Manhattan, Lincoln Park in Chicago, Hyde Park in London -- all of these are wildly successful urban parks not merely because of their beauty, but because of the high density of the neighborhoods that abut them. These parkside neighborhoods generally hold at least 50,000 people per square mile, roughly the density Jane Jacobs suggested as ideal. But this is yet another example of proper scaling: huge numbers of people require more space to spread out. If, following conventional wisdom, the Upper West Side is the traditional town writ large, then Central Park is the resulting exaggeration of courthouse square.

In addition to the incompatibility of Shelby Farms Park with its surroundings (in terms of creating a great urban park) there are issues of accessibility. The 754 square mile Shelby County, in which the majority of the Memphis area's residents reside, has a population density of just over 1,100 people per square mile. In short, the Memphis area is fairly spread out. With Shelby Farms Park located at the eastern edge of the metro -- 10 miles from downtown Memphis at the closest point -- the only access to the park for almost everyone in the region will be by private automobile. Even ignoring the implicit socioeconomic segregation, this location fails, through inaccessibility, to address any of the problems brought on by increased technology. It is merely a sprawling green space surrounded by sprawl. No matter what the park looks like, it will be accessible only to select people, and is unlikely to encourage an increased sense of community.

A few hundred miles to the north, another Mississippi River metropolis is struggling with an exacerbated version of the problems facing the Shelby Farms Park redesign. Mayor Slay and other residents of Saint Louis made news recently by suggesting that some of the national park surrounding the Gateway Arch -- the city's greatest landmark and monument to Manifest Desitny -- be redeveloped by reinstating the street grid that once ran right up to the riverfront and building a New Urbanist-style extension of downtown, complete with walkable condo-and-coffee-shop neighborhoodlettes. The merits of this project aside, it is interesting to note what the mayor and other St. Louisians describe as the somewhat infamously placid park's greatest problems:

it's hard to get to, and there is not much to do.In a park as large as Shelby Farms, a solid and cohesive landscape is next to impossible; any attempt would create extreme monotony. There will inevitably be a mix of landscapes surrounding specialized areas of activity. No matter how interesting or innovative they are these scattered points of interest will, at best, see the same fate as the Gateway Arch: they will become islands in an ocean of unused open space. But when all is said and done, what is most irritating about Shelby Farms Park is not that it will be nothing particularly special; there is no rule against gargantuan suburban parks. What is truly frustrating is that ths park claims that it can address the critical issues of landscape and public space in the 21st century, when at the most fundamental level, it cannot. Just call a spade a spade.

***

As we struggle to first define and then combat sprawl in the coming years, it will be interesting to see what kind of meaning that wretchedly overused and woefully misunderstood term -- "open space" -- takes on. It seems important to make some distinction between well-designed parks and public places (streets, riverfronts, plazas, etc.) and rural areas, and the wasted and/or misused areas that are so frivolously and irresponsibly labeled "precious open space" by reactionary neo-NIMBYs. Henceforth, "open space" will be used accordingly in posts at Where, while the well-designed places will be referred to either as "green space" or "public space," depending on their intended use.

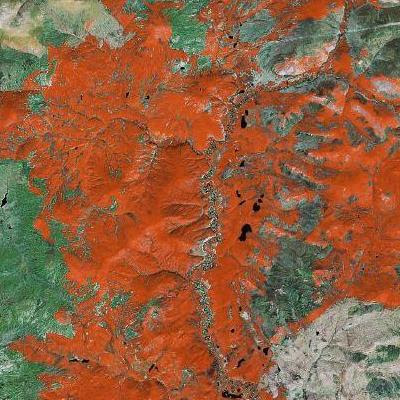

(Photo from Flickr user motus media.)

(Photo from Flickr user motus media.)Links:

Shelby Farms to Be a "21st-Century Park" (Architectural Record)America's Great 21st Century Park (CEOs for Cities)Shelby Farms Park AllianceShould the Landscape at the Arch Change? (STLtoday.com)

Lots of good reading for this weekend. Don't miss Item Six if you're a fan of absurd humor.

Lots of good reading for this weekend. Don't miss Item Six if you're a fan of absurd humor.